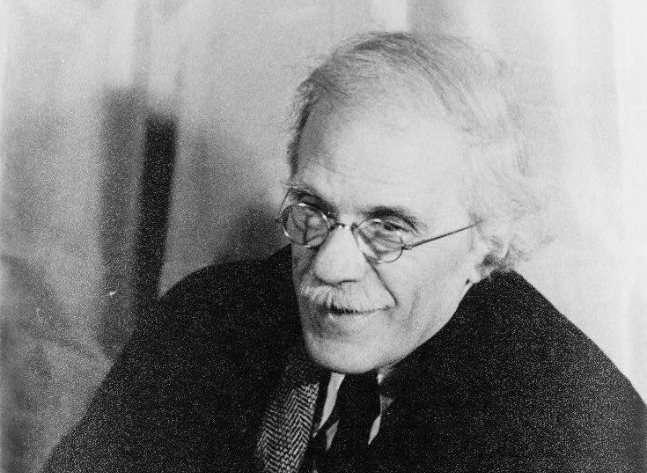

Alfred Stieglitz, 1938

Alfred Stieglitz was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, on the very first day of the year of 1864. His parents are a wealthy Jewish family that emigrated from Germany. Alfred Stieglitz was just eleven when he visited the local photo studio and watched the miracle of photos creation in the darkroom. There’s a legend that Alfred once saw a photographer retouching negatives. The old master explained to the young boy that retouching would make a person on the image look more natural. “You don’t need to do this”, – young Alfred said with no hesitation. Stieglitz’s biographers usually tell this story, to emphasize his legend. We don’t know if this happened for real, but the fact is that Stieglitz never retouched his negatives. Stieglitz’s photo ‘Steerage’ (find its story below) is among other Top 100 most influential pictures in human history.

Railways in Berlin, 1886

The Europian inspiration

The US-born Alfred Stieglitz bought his first camera in Berlin, Germany, where he spent his student’s years. He saw the camera on the shop shelf, and it utterly fascinated him. Photography was a student’s hobby, grew into a passion, and finally transformed into a professional career under the mentorship of Herman William Vogel, a professor of photochemistry.

Stieglitz traveled a lot and never left his camera. A young photographer captured peasants, fishers, and residents of the different European cities. People of various professions inspired him just like August Sander with his ‘People of the 20th century.’

Alfred’s creativity was testing the limits of the photo art; he continued his experiments consistently, looking to find his unique approach. He used a 24-hour exposure to take a photo of the car in the dark garage. The only light source was a dim lamp. Photo techniques fascinated Alfred more and more. He continued to develop his style and won silver medals at the competition of amateur photographers, in 1887 in London.

A rainy day in NYC, 1901

Back to the US

Alfred Stieglitz returned to New York, where he became a partner in ‘Photochrome Engraving Company.’ But his passion for photography didn’t go anywhere. Alfred continued his successful photo experiments and won around 150 awards in the US only. A talented workaholic, Stieglitz invested tons of resources and time in each image. He believed that a perfect picture requires a lot of prior research. Alfred studied the environment around the scene, lines of sight, various sources, and types of light. He was waiting for the complete harmony of the light, moving objects and other components to press the shutter on the camera. It’s quite similar to the famous ‘Decisive moment’ method of Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Sometimes Stieglitz was waiting for hours to take a picture. One of Stieglitz’s famous photographs, Fifth Avenue in Winter, was taken on February 22, 1893. The photographer spent three hours in an intense snowstorm until he found the perfect moment for a shot!

Snowy winter in New York, 1905

In 1893, Alfred Stiglitz took the position of editor-in-chief in ‘American Amateur Photographer’ magazine. His troublesome character led to immediate conflicts with the rest of the office, which considered the new boss to be too strict and autocratic. In 1896 he switched to another well-known magazine, “Camera Notes,” that was linked to the society of photography enthusiasts “The Camera Club of New York.”

Streets of Upper Manhattan, 1899

This publication suffered severe financial difficulties so that even authors and photographers (with rare exceptions) did not also receive an honorary. Sometimes editor even had to invest his funds to support the publishing. Fortunately, Stieglitz was rich enough to do so. After all, he managed an excellent platform to promote his photo ideas and to popularize himself and his friends as photographers.

Cloudy skies, 1910

The Steerage, 1907

‘The Steerage’ is an excellent example of his photos of Alfred Stieglitz that he widespread with Camera Club magazine. He captured this image during his voyage to Europe in 1907. Alfred was a kind of partial to social inequality that was a sure thing in the pre-WW1 world. He shared this feeling with many other photographers of the 20th century, like Weegee. But he managed to capture a perfect illustration of the terrible poverty when he left his first-class deck, went to ship’s steerage. There, the shawled and swathed were packed together on the compact lower deck, the minimalistic ship space stresses on overcrowded conditions and visually contrasting with those on the upper deck. “A round straw hat; the funnel leaning left, the stairway leaning right; the white drawbridge, its railings made of chain,” Stieglitz later wrote.

Gallery life

In early 1902, Charles De Kay, director of the National Arts Club, invited Alfred Stieglitz to organize a photo exhibition of contemporary American artists. Without any doubt, Stieglitz supposed that he would solely select the pictures for the show. He was its organizer, after all. But the whole photo community had a different point of view, and Stieglitz had to commit a cheap trick. He delegated the image selection to an initiative group, filled it with loyal photographers, and instructed to take a specific selection of works. Interestingly, this group went down in the history of photography under the name “Photo-Secession.”

A marvelous tree, a lake of Georgia, 1924

Alfred used this group name for his «Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession » gallery on 5th avenue. It was also known as “Gallery 291”, as it was located in building number 291. The gallery showed not only photographs but also works by contemporary artists, such as Cezanne, Renoir. Matisse, Mans, Rodin, Picasso, Braque …

The gallery had mixed success. The Matisse exposition, which took place in 1908, failed miserably, and even Stieglitz’s friends from Camera Club criticized it. The master’s resentment was so serious that he left the ranks of the group and never returned to it.

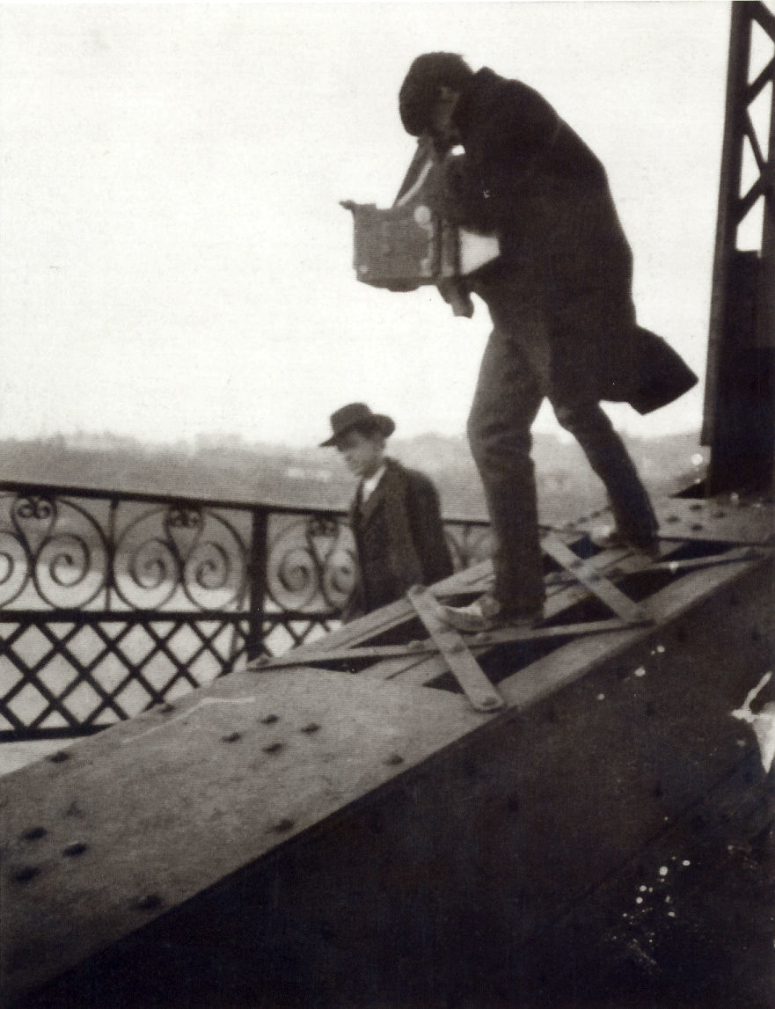

Alfred Stieglitz while taking a photo on a bridge, 1897

Picasso paintings exhibition (1911) was another gallery fail in Alfred Stieglitz’s biography. He recalled with pain that he sold only one drawing of the artist, that he drew when he was 12 years old. Stieglitz acquired it by himself. Alfred was so ashamed when returning unsold paintings to Picasso. They cost 20-30 dollars per one tapestry; the entire collection evaluation was just a couple of thousands of dollars. He offered these paintings to the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and he also refused to purchase Picasso’s works.

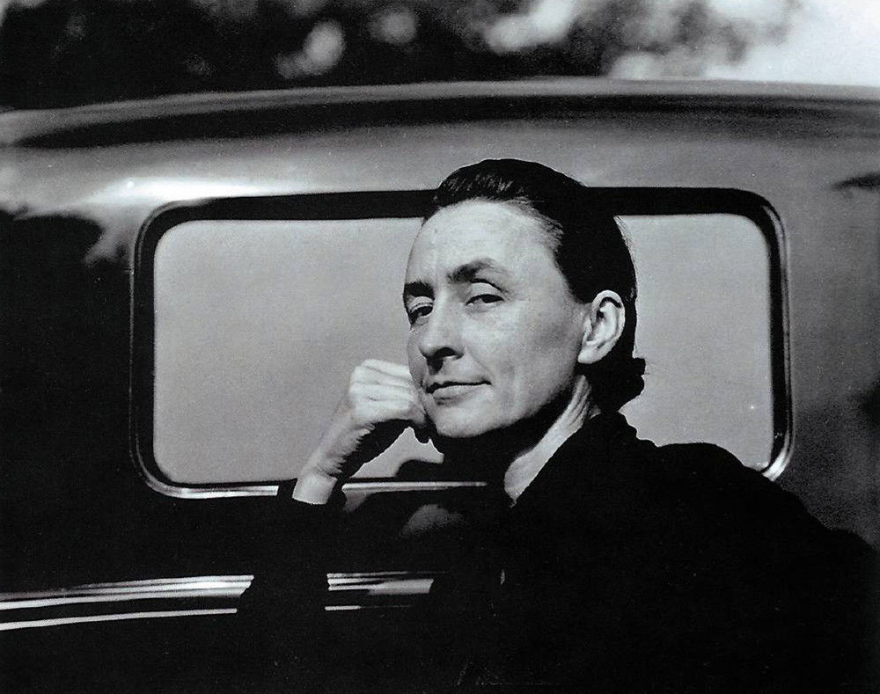

Georgia O’Keeffe, 1933

But you never know when life will surprise you. Stieglitz’s gallery venture wasn’t successful, but it met him with Georgia O’Keefe, his muse, friend, and wife. We’ll cover her influence on Alfred Stieglitz photography in a dedicated section on our site because their collaboration was unbelievably massive. Alfred Stieglitz made some of his best photos inspired by O’Keefe. Let’s just mention that photographer’s biographers agree that he received the second chance when he met Georgia O’Keefe. Alfred’s works got some inner fire, the energetic unseen before. He left hundreds of Georgia’s photos, and many of them are considered to be women portrait classics. Despite various life dramas and marriage nuances, O’Keefe was a person who spent with Stieglitz his last several hours of life. She organized funeral, cremated his body, and buried it in a secret place around the George lake area, where Georgia and Alfred spent their honeymoon.

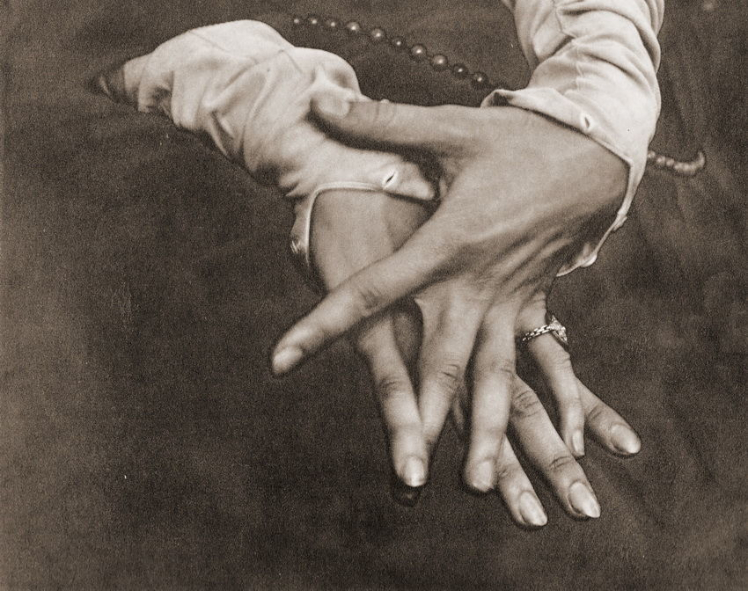

Georgia O’Keeffe’s hands, 1921

Alfred spent several hours in a snowstorm while he was waiting for a cab to pass by. 1905

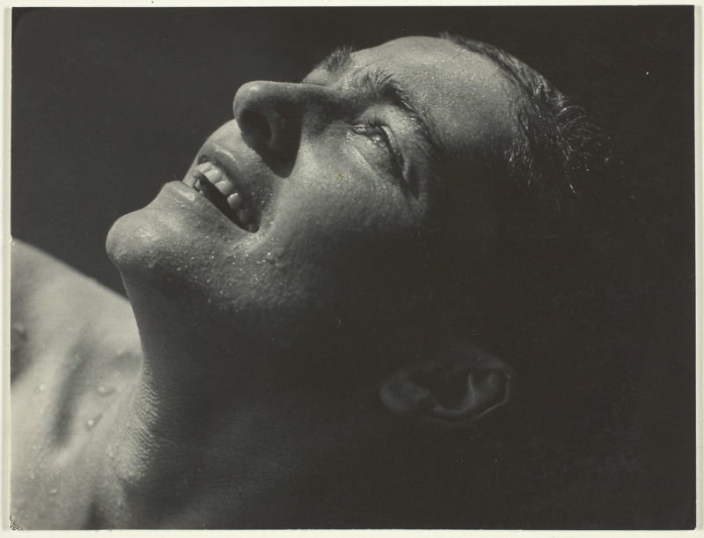

Swimmer, 1913

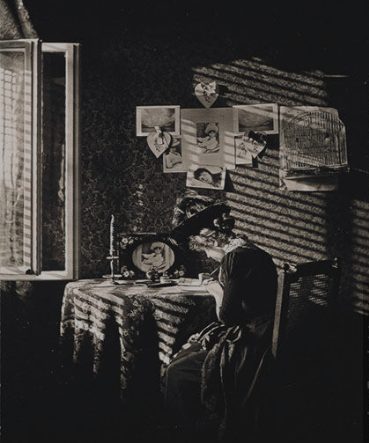

A woman writing a letter, 1899

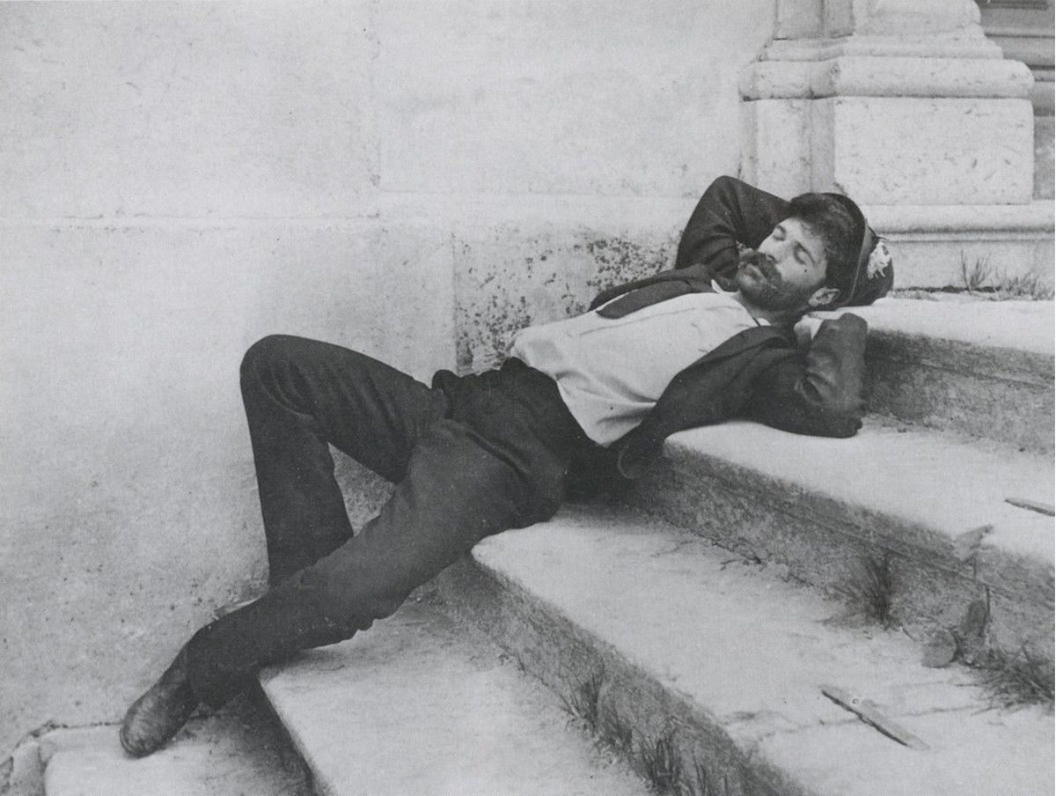

A sleeping craftsman during a break in New York, 1908

[…] A full story about this history photo […]