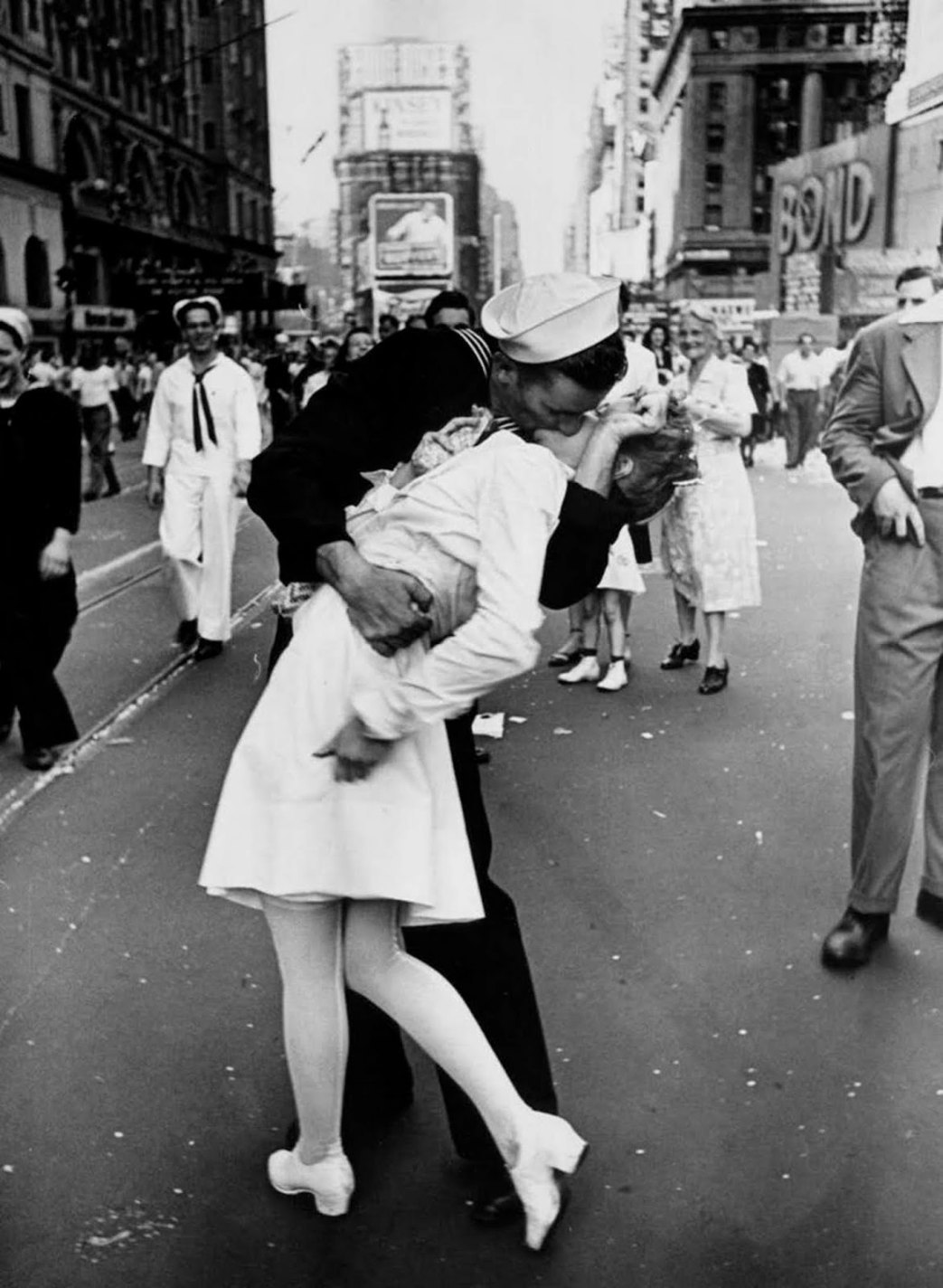

‘V-J Day in Times Square’ gained the same historical value as other Victory images like ‘Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima’ and ‘Flag over the Reichstag‘. All of these photos became the symbols of the victory in WW2. World War II cost the U.S. more than half a million people’s lives; almost 700 000 were injured. The day when Japan surrendered was glorious and historical for all American people. That’s why when this information spread, masses came out to celebrate the end of the war. Victory over Japan Day (V.J. Day) became a state holiday, and the most iconic symbol of this event in pop-culture is Alfred Eisenstaedt’s photo.

‘V-J Day in Times Square’ gained the same historical value as other Victory images like ‘Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima’ and ‘Flag over the Reichstag‘. All of these photos became the symbols of the victory in WW2. World War II cost the U.S. more than half a million people’s lives; almost 700 000 were injured. The day when Japan surrendered was glorious and historical for all American people. That’s why when this information spread, masses came out to celebrate the end of the war. Victory over Japan Day (V.J. Day) became a state holiday, and the most iconic symbol of this event in pop-culture is Alfred Eisenstaedt’s photo.

Alfred Eisenstaedt wasn’t the only photographer who took the ‘V-J Day in Times Square.’ There were plenty of cameramen on that day. Let’s take another photo by Victor Jorgensen: the same kissing couple on Times Square, but the angle is not so right. His image doesn’t show the magic of the moment as fine as Eisenstaedt’s photo did. So there’s no surprise ‘V-J Day in Times Square’ became iconic and occupied a place in the Top 100 most influential photos in history.

As Alfred Eisenstaedt said, “I noticed a sailor running along the street grabbing any and every girl in sight. I realized that it could do an exceptional image. So I was rushing ahead of him with my Leica looking back over my shoulder, taking dozens of pictures, but none of them were satisfying. Then suddenly, in a flash, I snapped something white that the sailor grabbed in his strong arms. I turned around and clicked the moment when he kissed the nurse. If she dressed in a dark skirt, I would never have taken the picture. I took exactly four pictures. It was done within a few moments.”

Even Eisenstaedt himself recognized that the massive part of his success was a bit pure luck.

But except apparent reasons. The story of the ‘V-J Day in Times Square’ is a little bit larger than one shot.

The background of the stilled moment

First of all, he is one of the first professional photographers who used a small and portable 35 mm film Leica camera. Nobody at that time took seriously small cameras, and this attitude helped Eisenstaedt to capture very natural expressions of his photo objects. His affection for Leica partially arose from his origin – Eisenstaedt was born and lived in Germany till 1935. He made a career as a documentary photographer in Europe. Several publishers (Associated Press, Illustrierte Zeitung) noticed his talent and acquired his photos regularly. He documented a meeting between Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini and took pictures of Joseph Goebbels. He emigrated to the U.S. with the rise of anti-jewish Nazi politics, just like Albert Einstein and many others did.

He fitted perfectly in the life of his new homeland and settled in New York. When President Truman announced the end of the war, Eisenstaedt came out on the streets hunting for a good picture. The “dancelike dip,” which “summed up the euphoria many Americans felt as the war came to a close,” drove his attention, and he took four frames. On one of them, the postures of a kissing couple created a dramatic composition.

LIFE of ‘V-J Day in Times Square’

LIFE magazine published the ‘V-J Day in Times Square,’ and this image became one of the most famous Eisenstaedt creations.

Hidden faces, contrast clothing, made characters unified: the one military who returned from war and the one who was waiting at home.

Identification of the persons from the photo became an obsession for many journalists. Many people arrived at LIFE’s office and claimed to be a couple from the picture. As a result of the careful investigation, knowledge of the exact time when Eisenstaedt pressed the shutter, many pretenders failed to get publicity.

Historians still have doubts about the personalities of the sailor and nurse. In 2012 researchers claimed that their names were George Mendonsa and Greta Zimmer Friedman. But these facts are still uncertain, due to the number of sailors who grabbed and kissed random women during the V-J Day celebration. The person of Mendonsa was identified due to his scars and tattoos, and Zimmer was recognized due to her height and dental hygienist uniform.

The photo became a cultural phenomenon: it inspired the creation of several statues, was used as a cameo in cartoons (The Simpsons) and movies (Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian, Watchmen, Letters to Juliet), appeared in video games (Wolfenstein: The New Order).

Except for cultural meaning, the photo rose a question of the public percipience of a sexual assault. This issue relies not only on the picture: many women suffered the assaults by the drunk sailors, soldiers grabbed and kissed girls without permission.

Sexual assault or victory emotions?

Greta Zimmer Fridman said that “A sailor grabbed me and it wasn’t that much of a kiss, it was more of a happy act that he didn’t have to go back to war. And the reason he grabbed someone dressed as a nurse was that he just felt very grateful to nurses who took care of the wounded. I felt he was powerful; he was just holding me tight. I’m not sure about the kiss because, you know, it was just somebody celebrating. But it wasn’t a romantic event. It was just an event of thanking God the war is over kind of thing,” adding that “it wasn’t my choice to be kissed. The guy just came over and kissed or grabbed.”

After Mendosa’s death, someone scribbled graffiti on the statue in Sarasota: #MeToo, but publicity and social media didn’t support this point of view.

As for the photographer, Alfred Eisenstaedt lived long and died at the age of 96 in his “Pilot House” cottage.

[…] history of the Tokyo-based Casio Computer Co began in 1946, right after the end of WWII. Four brothers – Toshio Kashio, Kazuo Kashio, Tadao Kashio, and Yukio Kashio – […]